As we move education into a realm that makes greater use of online learning and we ponder how we award traditional course credit for courses taken in the MOOC model, an important consideration is our ability to verify that the person receiving the credit truly is the person doing the work.

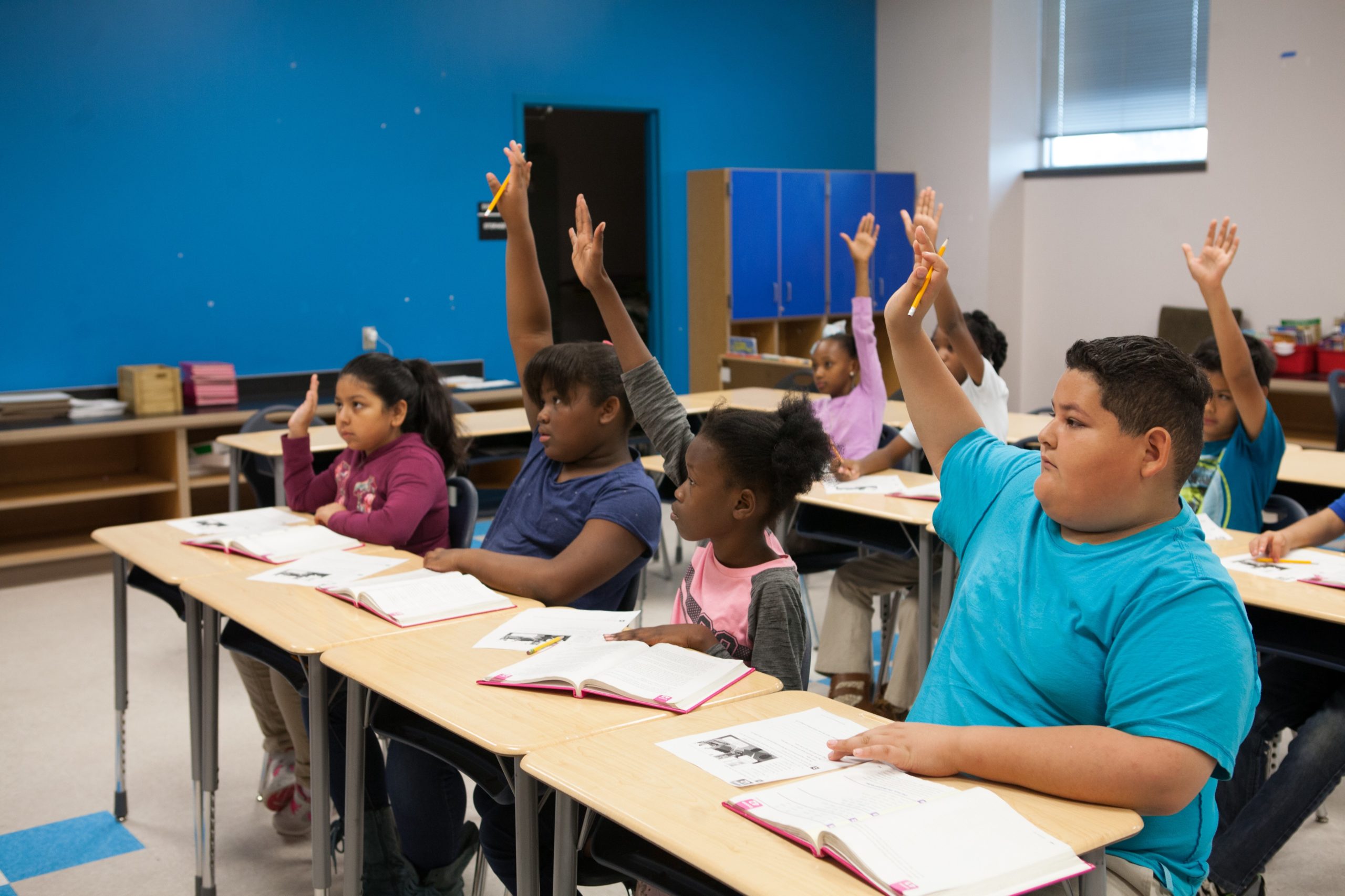

An obvious advantage that the traditional face-to-face education model has over online environments is that it’s relatively easy to gauge a student’s understanding and confirm that the person sitting in class, participating in a discussion or taking a test is actually who they say they are. The online environment presents some unique challenges in this regard: Anyone who saw the news earlier this year about Notre Dame football player Manti Te’o’s non-existent girlfriend is familiar with the concept of “catfishing” and the difficulty in validating that the person on the other end of a discussion board is who they claim to be. If such impersonation occurs in social settings where the stakes might be considered relatively low, is it unreasonable to assume that such impersonations will occur in an environment where the rewards are potentially much greater? We’re talking about awarding educational credentials that can lead to greater employment opportunities and/or higher salaries—big payoffs.

Some organizations, including Northeastern, are investigating methods to validate student identity, including remote proctoring services (for example, using the student’s video camera to record the student taking the exam) and other technology-based systems. In addition, we have tools that help to identify plagiarism such as the TurnItIn system, which we use here at the Northeastern College of Professional Studies (CPS).

All of these potential solutions rely on a human being (the professor) to validate the results and determine if further investigation is necessary. It’s also up to the professor to ensure that students are not unnecessarily investigated and penalized. Just how useful these solutions will be in an environment that relies on peer feedback mechanisms for assessment of student learning (where students grade each other against an instructor-defined rubric) is very much open to question. Some might argue that peers are more likely to identify questionable activities and be able to verify student identities without the need for technological oversight. But identity hoaxes may be hard to detect and are often accompanied by documentary “proof” (assignment work) that is difficult to distinguish from the real thing.

Much work remains to be done before we can feel comfortable that the person receiving a credential after taking online courses is actually the person who deserves it. We certainly have technology that can form the basis for identity validation, like facial recognition, and we can use audio and video recording tools to capture student-testing environments. A larger question to ponder is whether the cost of a widespread implementation of technologies like these, along with the required human validation of the results, may dwarf the cost and detract from the many benefits that accompany the MOOC model.

Manti Te’o’s fake girlfriend sent shockwaves through the NFL. What impact might fake students have on higher education? Only time will tell.